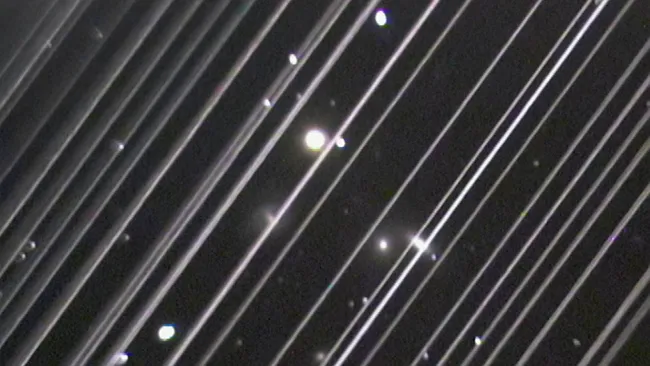

SpaceX’s Starlink satellites, designed to provide global internet coverage, are now causing significant issues for astronomers.

Researchers have discovered that the latest generation of these satellites, called V2-mini, emit 32 times more radio noise than their predecessors.

This increased noise is interfering with radio astronomy observations, a crucial method for studying celestial objects and phenomena.

Radio astronomy relies on highly sensitive antennas to detect faint radio signals from space, which are emitted by stars, black holes, and other cosmic entities.

Scientists working at the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) in the Netherlands, one of the world’s most sensitive radio observatories, have been particularly affected.

They found that the Starlink satellites appear up to 10 million times brighter than some of the most vital research targets, making observations of distant exoplanets and nascent black holes increasingly difficult.

Jessica Dempsey, director of the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, highlighted the severity of the issue.

She mentioned that the unwanted radio emissions from these satellites could obscure faint radiation from the Epoch of Reionization, a significant period in the universe’s history.

This epoch began about one billion years after the Big Bang, and the low-frequency radio waves it emitted can only be detected by the most sensitive radio telescopes.

During observations in July, researchers noticed the V2-mini satellites’ noise was up to 1,000 times above the previous limits, making matters worse for radio observations.

The LOFAR antennas, usually protected by radio quiet zones that restrict low-frequency emissions, are not safeguarded against noise from above, which is currently unregulated.

With more than 6,300 active Starlink satellites and plans to launch over 40,000 more, this interference is set to become ubiquitous.

This situation also poses risks for the Square Kilometer Array Observatory (SKAO), the world’s largest and most sensitive radio telescope under construction in Australia and South Africa.

The SKAO will have eight times the sensitivity of LOFAR and, thus, be eight times more vulnerable to this interference.

The project, costing $2.2 billion, is expected to be operational by the end of this decade.

Despite the benefits of Starlink satellites, such as providing fast internet to remote locations, their operation comes at a steep cost for astronomical research.

Dempsey explained that while the satellites improve connectivity, they significantly limit the observable universe from Earth-based telescopes.

The research team found that the radiation levels from V2-mini satellites exceed the International Telecommunications Union’s regulations.

This excessive radiation is like comparing the faintest stars seen by the naked eye to the brightness of the full Moon, according to lead author Cees Bassa.

With SpaceX launching about 40 second-generation Starlink satellites every week, this problem is expected to worsen.

Federico Di Vruno, spectrum manager at SKAO, emphasized the need for immediate action to preserve the ability to explore the universe from Earth.

He noted that minimizing unintended satellite radiation should be a priority for sustainable space policies.

SpaceX began launching the V2-mini satellites in February 2023.

These new satellites are twice as large as the earlier models and include more powerful electronics and antennas for better connectivity.

However, the increased capabilities bring about significant unintended consequences for radio astronomy.

Professor Robert Massey from the Royal Astronomical Society echoed the call for urgent action. He stated that while some may dismiss the importance of certain astronomical research, it often lays the foundation for fundamental and crucial scientific discoveries with long-term applications.

Without proper regulation and mitigation measures, the proliferation of satellites may soon overwhelm ground-based astronomy in every wavelength, posing an existential threat to this field.

Simple solutions, such as shielding satellite batteries, could significantly reduce radiation emissions, but collaborative efforts are essential to address this growing issue.

The findings were published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, underscoring the urgent need for regulatory standards that limit satellite emissions to protect astronomical research.