NASA finds itself at a pivotal juncture as it plans for the future of human activity in low-Earth orbit beyond the lifespan of the International Space Station (ISS).

With the ISS expected to retire around 2030, the U.S. space agency is charting a course toward commercial space stations.

However, this transition from government-operated missions to commercial partnerships is fraught with uncertainty and challenge.

In an interview, Deputy Administrator Pam Melroy emphasized the continued importance of human presence in low-Earth orbit for scientific research, particularly studies related to microgravity and long-term space travel.

She believes that moving away from the ISS doesn’t diminish its significance; rather, it paves the way for more ambitious missions as part of the Artemis Program aimed at exploring the Moon and Mars.

Nasa has been expanding the capabilities of the ISS over the past years, using it as a crucial platform for understanding the risks associated with long-duration spaceflights, which are essential for future Mars missions.

Key areas of research include microgravity impacts on human health and perfecting life-support systems that recycle resources efficiently.

As NASA finalizes its strategy to operate beyond the International Space Station, it has been collaborating with private entities since 2018 through the Commercial LEO Destinations (CLD) program.

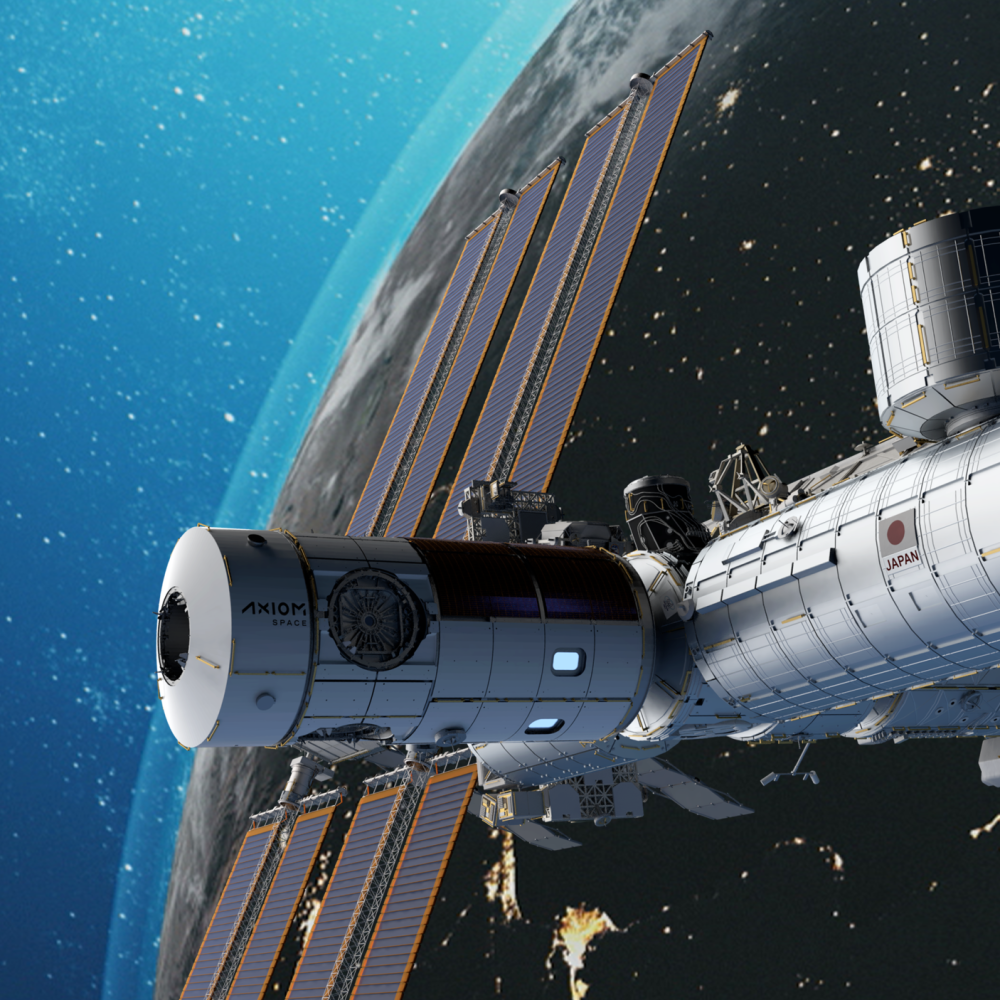

Contracts worth millions were awarded to companies like Axiom Space and Blue Origin to develop commercial platforms.

However, the journey hasn’t been smooth.

Financial challenges and doubts about business viability have plagued these efforts, casting shadows on the program’s future.

While companies like Voyager Space and Axiom have emerged as participants, their futures are not guaranteed.

Funding and commitment levels from NASA are variables that might affect outcomes.

Even as NASA prepares to issue requests for proposals for the next phase of the CLD program, potential entrants like SpaceX and Vast Space add to the unpredictability.

Congress’s fluctuating support complicates matters further.

Despite some financial increases in recent years, the initial underfunding of the program reflects broader hesitations about its priority.

Numbers from fiscal years show the program’s inconsistent funding path, with requests and allocations often not aligning.

The possibility of a gap in human presence in orbit, should plans falter, exists.

NASA sources acknowledge potential delays, with Phil McAlister commenting that while a gap would be undesirable, it could be manageable with solutions like Crew Dragon and Starliner vehicles.

Beyond NASA’s commitment, the viability of commercial stations hinges on establishing demand beyond government use.

The 2017 study suggested a cautious outlook, noting the absence of a distinct, profitable industry trend for space activity.

As NASA seeks to move from an anchor customer to one among many, uncertainties over user demand and competition from automated technologies linger.

Companies like Varda are exploring automated manufacturing solutions, potentially diminishing the necessity of human-run stations.

Ultimately, NASA’s strategy will require robust backing if it aims to transition successfully to commercial habitats.

Establishing safe, functional stations is essential, albeit they must avoid the timeframe and cost concerns associated with the ISS.