The enigmatic nature of black holes has puzzled scientists for decades, giving rise to numerous paradoxes and theories.

However, a recent study presents a groundbreaking alternative: what if black holes are not what we think they are but rather ‘frozen stars’?

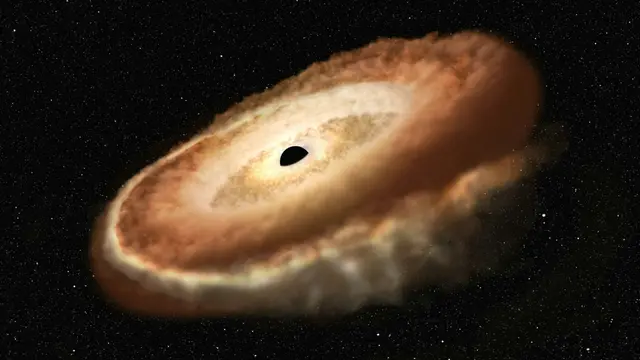

Black holes, according to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, are characterized by having an infinitely dense point known as a singularity and an event horizon—a boundary from which nothing, not even light, can escape.

Yet, these defining features have led to several unresolved paradoxes that cast doubt on our current understanding.

One of the most compelling paradoxes is Stephen Hawking’s radiation paradox.

According to Hawking, black holes emit radiation that causes them to lose mass over time and eventually evaporate.

This contradicts the principle that nothing can escape from a black hole, violating the conservation of information—a cornerstone of quantum mechanics.

The new study conducted by researchers at Ben-Gurion University in Israel offers a fascinating solution: black holes might actually be ‘frozen stars.’

These objects are theoretical remnants of stars that have cooled down, no longer emitting light or heat, and are sometimes referred to as black dwarfs.

Normally, stars are believed to take trillions of years to reach this ‘frozen’ stage.

Given that our universe is only 13.7 billion years old, such stars shouldn’t exist yet.

However, the study draws detailed comparisons between the thermodynamic properties of frozen stars and black holes, showing that many of the paradoxes associated with black holes disappear under this new model.

Ramy Brustein, the study’s first author, elucidates that frozen stars lack both singularity and event horizon.

They are ultracompact and can mimic the observable properties of black holes without their troublesome theoretical features.

For example, they can emit radiation and gravitational waves, aligning with Hawking’s radiation theory but without violating principles of quantum mechanics.

The idea of black holes as ‘frozen stars’ also aligns with the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which prevents particles from being squeezed into an infinitely small space.

This quantum pressure could explain why singularities don’t form and why these objects remain finite.

This theory could potentially shake the foundations of modern astrophysics and demand significant modifications to Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

However, it’s essential to note that this hypothesis still faces several challenges and limitations.

For one, black dwarfs theoretically possess an internal structure, unlike traditional black holes.

Additionally, no experimental evidence currently exists to confirm that black holes are indeed frozen stars.

While this hypothesis offers exciting prospects, much more research is needed to validate or refute it thoroughly.

Nevertheless, the study, published in the journal Physical Review D, opens promising new avenues for understanding the mysterious nature of black holes and could lead to revolutionary advancements in our knowledge of the universe.